While browsing the shelves in the Rare Book Room, I came across this 1887 edition of The Comic Blackstone, originally published in London in 1846 and written by Gilbert Abbott à Beckett. This edition was revised and expanded by Gilbert's son, Arthur William à Beckett, who, like his father, was a barrister at Gray’s Inn. The Comic Blackstone is a parody of William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England. Like that famous work, this one consists of an introduction and Parts I–IV (The Rights of Persons, The Rights of Things, Of Private Wrongs, and Of Public Wrongs).

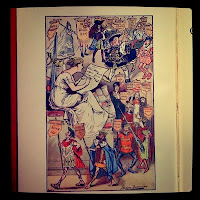

The ten full-page colored illustrations in this edition are by Harry Furniss, and include the illustration to the right, entitled "The Study of the Law." A woman appears to be taking notes on the history of the law, as a parade of characters marches backward in time--from Queen Victoria and the Comic Blackstone in the upper left-hand corner to Julius Caesar and Roman law in the bottom left-hand corner. The book is bound in a highly decorative cloth that represents a trend in nineteenth century England and America; it was previously featured in a Spring 2010 exhibit called "Books and Their Covers: Decorative Bindings, Beautiful Books," curated by Karen Beck.